🎉 Welcome to my newsletter, The Boy Who Bakes, a subscriber-supported newsletter, dedicated to all things baked. This is a post for paid subscribers, who receive exclusive weekly recipes. You can become a paid subscriber to get access to this recipe and every recipe moving forward plus you’ll also get access to the archive including every recipe posted on the newsletter. It costs just £5 a month and that helps me continue writing this newsletter. To subscribe, to either the paid or free newsletter, click the link below. 🎉

Hello. Happy Friday!

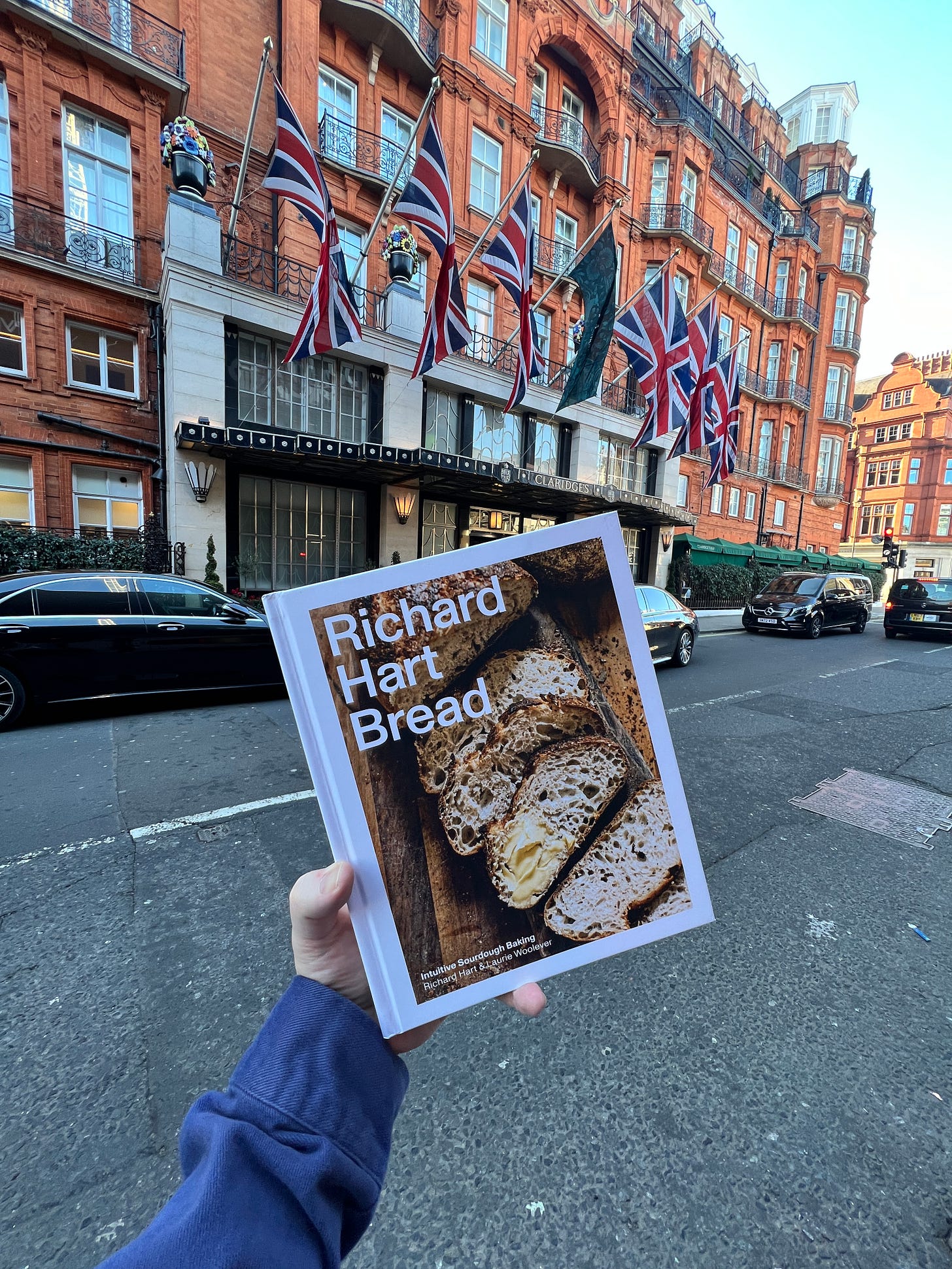

It has been a busy old week. I started it slipping and sliding around a very muddy New Forest, getting a little lost in the dense forest, and then ended it at a champagne breakfast at Claridge’s. Talk about polar opposites. It is also still rhubarb season, and I couldn’t really resist doing one more week dedicated to my favourite winter produce.

Richard Hart

If you are into bread baking or have visited Copenhagen, you’ll likely know the name Richard Hart. A baker from London, he was, for a long time, the head baker at Tartine in San Francisco, and then after working with Rene Redzepi, he opened the Hart Bageri chain of bakeries in Copenhagen. He is one of the most well-regarded bread bakers working today and, strangely enough, has never opened a bakery back on his home turf, until now, that is. Earlier this week I popped along to Claridge’s to attend a breakfast to celebrate the launch of his new book, Richard Hart Bread. At this breakfast, Hart and the hotel announced they’d be opening a new project together later this summer, to be called Claridges British Bakery. The bakery will avoid the current trend of cookie-cutter bakeries that make laminated pastries and instead focus on British baking heritage, which, to be honest, sounds quite refreshing. I hate to admit it, but I am beginning to get a little bored of the conveyor belt of bakeries that have opened in the last few years that just seem to make the same products as every other new bakery, and I am excited for a new direction and something a little bit different. Don’t get me wrong; many of these new bakeries are excellent, and some make outstandingly good products (hello Lannan in Edinburgh), but not every bakery needs to follow the same blueprint. A bit of variety is surely a good thing? Richard said the reason he wanted to go back to his British roots is because he was bored of finding the same style of pastry wherever he was in the world, so I am excited to see what his interpretation of a British bakery will be. Bring on summer 2025.

Rhubarb Jam

It is rhubarb season here in the UK, so not only do I have a fabulous new recipe for paid subscribers, but I thought I would also post my go-to rhubarb jam recipe, which I make every year. The jam is incredibly easy to make and just uses vanilla as additional flavouring.

Rhubarb and Vanilla Jam

Makes 5x340g jars

This jam is, obviously, made with rhubarb, which has a very low pectin content. As I am not using jam sugar or adding pectin separately, you’ll find this jam sets quite loosely, which I find to be perfect for rhubarb. It then works great in place of a compote on things like rice pudding whilst still working on your toast in the morning.

1kg forced rhubarb, cut into small chunks

Juice of 1 lemon

800g caster sugar

1 vanilla pod

Before you start the jam, first sterilise the jars. Preheat the oven to 160ºC (140ºC Fan) and wash the jars in hot soapy water before rinsing out, but not drying. Place the jars onto a baking tray and pop them in the oven for 10 minutes, at which point the jars should be dry. For the lids, pop those in a bowl of boiling water and leave to soak for a few minutes; set aside until ready to use.

Pop a couple of side plates in the freezer.

Add the rhubarb to a large stockpot, along with the lemon juice, and cook over medium heat until the rhubarb starts to soften. Add the sugar and seeds scraped from the vanilla, along with the pod itself, to the rhubarb and cook for a couple of minutes or until the sugar is no longer visible and you have a pot of very juicy-looking rhubarb. Turn the heat up to high and cook for about 10 minutes, stirring occasionally, or until the jam reaches setting point.

To test the jam has been cooked to the right temperature, there are a few different methods you can use. Firstly, you can use a jam or candy thermometer and check that the temperature reaches between 104ºC and 105ºC. Secondly, you can use the wrinkle test. For this method, I find it useful to start testing after about 6 minutes of cooking. Take one of the frozen side plates from the freezer and spoon a small amount of jam onto the plate and pop it back in the freezer for 30-60 seconds. Use your finger to push through the jam. If the jam wrinkles when pushed, it has reached setting point, and you can stop cooking. If the jam still seems liquid and loose, cook a little further, testing as you go.

Once cooked to the correct temperature, let the jam sit for a couple of minutes before carefully decanting into the still-warm sterilised jars, sealing immediately. Once sealed, the jam will keep for 6 months; once opened, they should be stored in the fridge and used within a few weeks.

Rhubarb and Vanilla Panna Cotta with Burnt Honey Cream

Serves 4-6

If you want an incredibly easy dessert that seems sophisticated and, dare I say, ‘cheffy’, this panna cotta might just do the trick. If you’ve never made a panna cotta before, just know that it is one of the easiest desserts you can make. At its heart, it is simply a mixture of dairy that is lightly sweetened and set with gelatine. Unlike baked custards like crème brûlée, panna cotta is unbelievably light and not too rich at all. In this version the cream is flavoured very simply with vanilla, but it is served with two delicious complementary elements, namely roasted rhubarb and a burnt honey cream.

For me, the mark of a stellar panna cotta is one that is just barely set, a panna cotta that will collapse if looked at in the wrong way, a panna cotta that has a wobble that might be considered indecent. Traditionally, if you’re making a panna cotta that is moulded, you can use less gelatine because the mould itself fully contains the dessert. If you want to turn the panna cotta out onto a plate, you’d traditionally use a little more gelatin so that the dessert holds its shape. In my recipe I like to use the bare minimum amount of gelatine that I can get away with so that the cream melts in the mouth and there isn’t even a hint of rubberiness. Because I like to pair back the gelatine to its minimum, I use the same amount whether I’m serving it inside the mould or turned out onto a plate. If you like the dessert to have a little more body, you can always increase the amount used by an extra 1/2 sheet should you wish.

Gelatine

Before we get to the recipe, let me clear up some confusion around gelatine sheets, which is what I predominantly use.

I generally list gelatine by the number of sheets needed. Not the weight of the sheets and not the strength of the sheets. This can seem confusing to some because the sheets of different brands might have different strengths, like bronze strength or platinum strength. The reason I don't give any further detail is because as long as you’re using sheet gelatine, one sheet will always set the same amount regardless of the brand or the supposed strength, which I know sounds counterintuitive and confusing.

Gelatine comes in a variety of grades, such as Bronze, which has a stated bloom strength of 125, or Platinum, with a bloom strength of 250. Bloom strength refers to the setting power of each type of gelatine. Does this mean that you need half as many platinum sheets compared with bronze? The simple answer is no. Because those sheets also weigh different amounts and are ultimately designed to set the same amount of liquid across the board. So whilst bronze gelatine is ‘weaker’ than platinum, the sheets are thicker and weigh more to ensure the same finish. This means that if a recipe calls for 2 sheets of bronze but you have 2 sheets of platinum, you can substitute 1:1. The same is not quite true when going by weight. If a recipe calls for 10g platinum gelatine, you can't use a simple 1:1 substitution and just use 10g bronze. If the recipe doesn't also state how many sheets are called for, this handy chart is worthwhile bookmarking for reference.

Thankfully in the UK, platinum gelatine is about all that is available in the major supermarkets, so if the recipe is vague, you could be confident this is what they used.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Boy Who Bakes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.